Winning starts with what you know

The new version 18 offers completely new possibilities for chess training and analysis: playing style analysis, search for strategic themes, access to 6 billion Lichess games, player preparation by matching Lichess games, download Chess.com games with built-in API, built-in cloud engine and much more.

When Magnus Carlsen became the world chess champion a few days ago, I don’t think anyone in the chess world lost money. All bets were on the almost-twenty-three-year-old Norwegian’s beating the reigning grandmaster, Viswanathan Anand. With play in Chennai, India, Anand had the home-court advantage, but, at nearly forty-four, he is getting old for top-level chess, and Carlsen gained momentum as the match went on. He didn’t lose in ten games. Perhaps the biggest surprise was in the last one, when Carlsen, with the prize in his grasp, played to win rather than accepting what looked to be Anand’s offer of a draw, which would have clinched it for Carlsen anyway. He could have been the world champion a couple of hours sooner.

Or even a year earlier. Carlsen, whom I wrote about for the magazine in 2011, had skipped the previous world championship in 2012, objecting to the way in which the qualifying matches were conducted, and so, as it turns out, forewent the chance to be the youngest world champion ever.

But, in the meantime, his FIDE rating, the chess world’s mathematical system for ranking tournament players, had continued to rise, and even before he and Anand settled into their chairs, his was the highest in history, surpassing even that of Garry Kasparov, who, starting in 2009, had coached him for about a year—before Carlsen decided that the passionate Russian got him too hepped up to enjoy the game. (Kasparov, for his part, threw his hands up at Carlsen’s casual approach to training, telling me back in 2011 that he “was not in a position to make him change his personality.”) But Kasparov was always impressed by Carlsen’s intense will, and, after the Chennai match, told me that he wasn’t surprised that Carlsen went for the outright victory instead of settling for a draw in the final game: “He likes to play, he likes to win, and he had the better position. He’s a maximalist like Fischer, and he expects to fight to the death.” (In this particular game, Anand salvaged a draw.)

You had plenty of positives to look at from the first four games. After the third game, you said, your upside was not adequate enough to force a win. After detailed analysis, do you still have the same view?

I definitely feel it was a mistake that I underestimated my possibilities in that game. It was a mistake. He (Carlsen) mentioned it as well that he thought I had let him off the hook so easily. Well, that I more or less concede. I agree. I should have pressed him a bit more. Thereafter, I atoned by escaping, in Game Four, the way I did. It was a nice defence. The problem was that after Game Four I thought we were really into the match. We were warmed up and it was going to get exciting. But we know what happened next.

Where did you lose the thread in the Game Five?

Actually, it was throughout the game, I mean, there were small mistakes, here and there. I didn’t lose the game in one move. I lost it over several and it’s exactly what I had hoped not to do but it was exactly what I did. So Game Five was one of those losses which hurt because you do it bit by bit. Not one blunder, but the game slips away from you.

Going by your body language during this game, is it fair to conclude that you were getting increasingly annoyed with yourself due to the choices you were making? You appeared to make some random moves, as well.

Yes. It is quite perceptive. I think, it’s clear I could feel I was making small mistakes and that was getting annoying. But you have to still get a grip on yourself because there is no use crying over split milk and all that. You have to get your thoughts back to the game but there was residue of annoyance. At every moment, I knew that had I been more precise earlier, it could have gone better or have been easier.

Would you say your vast experience failed you, when it mattered, in the match?

Yes. I think so. Your strength comes into play when you are able to stop your opponent playing to his strengths. But I never really succeeded in doing that or only did that briefly. In the end, he was just stronger and he was able to impose his style of play.

In my interview, Magnus Carlsen said he had planned to make you play slow, long games and force the errors. Was his energy-level in the fifth and sixth hours of play decisive since he continued to find moves of optimum strength?

Yes. I mean, I never really adapted to his style well. Clearly, he has refined his style a lot recently. He has become stronger and more effective with it. So, I also had this feeling that if I had managed to pull it off, it would have been a different story. But I didn’t manage to get a grip on his style.

Having brought Carlsen under pressure from the start of Game Nine, mainly due to your decision to open the game with d4 (pushing the queen-pawn to the fourth rank), do you regret not doing so in the earlier games with white pieces?

Yes. But I made a big strategic decision to focus on e4 (pushing the king-pawn to the fourth rank). In hindsight, that was the worst move of the match. Again (smiles) in hindsight, many things are clear. For this match, for some reason, I just felt it was simpler to play e4 and there were grounds for it. Based on my tournament results and all, I felt it was better to concentrate on e4. And it turned out to be a bad mistake.

Viswanathan Anand has accomplished everything that a chess player could possibly want to. He has been a five-time world champion and in three different formats. He was the undisputed world champion for six years. He has been the world number one, and also the single biggest reason for a chess renaissance in his country. And he has been a tremendous ambassador for the game, having played at the elite level for well over a quarter of a century. He simply has nothing left to prove.

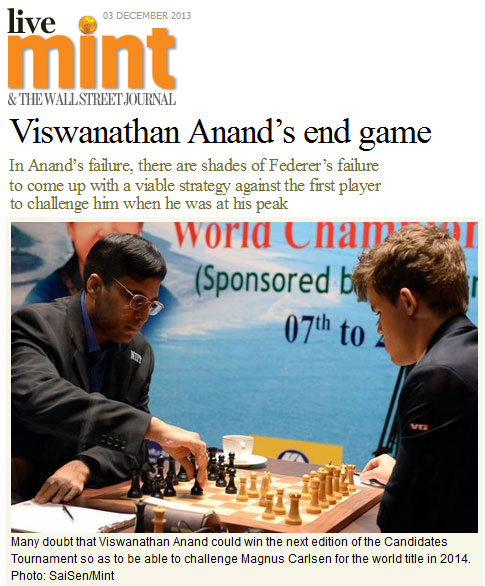

But today, as he turns 44 in a couple of weeks, he’s no longer the world champion. Many doubt that he could win the next edition of the Candidates Tournament so as to be able to challenge Magnus Carlsen for the world title in 2014. If his match play in the recently concluded world championship battle with Carlsen in Chennai is any indication, then Anand’s form is in clear decline. Grandmasters the world over have remarked how uncharacteristic were the blunders he made that eventually cost him the world title.

The first clue that the champion was not at his prime any more was, of course, his strategy against the world number one. In his previous world title matches, Anand played to his strengths: his legendary opening repertoire and his supremacy in rapid chess. He played safe, and kept drawing games, knowing full well that if the scores were level at the end of the regular format, he could demolish the opponent in the tie-break or rapid games that would follow. Fully aware of this, and faced with draw after draw as the match progressed, his opponent would be forced to take more and more risks to force a victory and avoid a tie-break. In the process, in the later games, he would end up making mistakes, and play into Anand’s hands. This plan worked superbly against Veselin Topalov and Boris Gelfand. But it was never going to work against Carlsen. Yet Anand did not or could not move away from his tried and tested strategy.

So, rather than make his strengths count, by focusing on dictating the game through his superior opening preparations—which also happens to be the one area Carlsen could not match him—Anand chose to try and match Carlsen in end game wizardry. To his credit, he did manage to compete on an almost equal footing. But unfortunately he did not—and some would say, could not—have the staying power of someone two decades his junior.

The second problem Anand had was that Carlsen does not like to draw. He would rather play on and on for eternity in the expectation of squeezing out some advantage rather than settle for a draw. This meant that, from having to work hard for a win, Anand now found himself working hard for a draw—not exactly what you would expect of a world champion. And this is where the psychological battle was won by Carlsen. He has said as much in his many interviews—once he saw that the world champion was as nervous as he was, and playing conservative chess, the challenger knew he could relax and play his normal game, which he went on to do with devastating effect.

In Anand’s failure, there are shades of Roger Federer’s failure to come up with a viable strategy against the first player to challenge him when he was still at his peak—a younger, fitter and stronger Rafael Nadal. The only blemish in Federer’s glorious record is his failure to respond as a champion and stamp his superiority over Nadal. This failure, many would argue, has more to do with his mind than his game. Federer inevitably ended up playing to Nadal’s strengths—engaging in long rallies where the latter would eventually wear him out. Carlsen did the same to Anand. Just as Nadal kept the ball in play till the master committed an error, or ceded an opening for a winner, Carlsen kept moving the pieces around accurately till the champion made an error.

Magnus Carlsen has, at various points, mentioned that once he sits down on the chess board he doesn’t believe that anyone could beat him. He carried that same confidence into the World Championship match too. What were your thoughts at the start of the match? Did you feel invincible too?

I thought that if I had a good start, I would be able to play well. I thought that if I had a good start, I could force him out of his comfort zones. I was under no illusions that I would have to raise my game – but that’s exactly what I had worked so hard for. I knew I had a chance. I knew my recent shape had not been very good. But I was hoping that I had managed to turn all that around.

A match like this is always tough. In the sense, it almost feels like you are locked in a cage at times. At what point did you think it was over for you?

Well, it was staggered. The first few games were probably okay. I thought I held my own. The fifth game (his endgame errors cost game five) loss hit me really hard. It was precisely the thing that I had worked so hard on; the areas that I had sought to improve in my preparation and I was unable to execute. In that sense, I failed. The 9th game blunder didn’t change things very much – I didn’t see a win, it would have been a draw. The 10th game was really nothing.

So what is it about Carlsen? Did any aspect of his game surprise you?

He surprised me by changing so little. I know how he plays. But I expected him to come out and try something different. But he stuck to his guns – it was brave. It was also unexpected for me. Usually for a World Championship match, people work on something different… maybe something to surprise the opponent. Carlsen just stayed the same.

You have said that you couldn’t figure out Carlsen’s style. What does that mean?

I thought I could get a grip on him. I thought that I could force him to make mistakes. I thought that if I stayed with him in the early going, I would be able to match him. But his style makes it difficult. In a sense, he is an allrounder. He can do everything well and he makes mistakes – but they aren’t big enough to take advantage of. He is also unconventional – there are times when he will play something and take it back on the next move… to the same place.

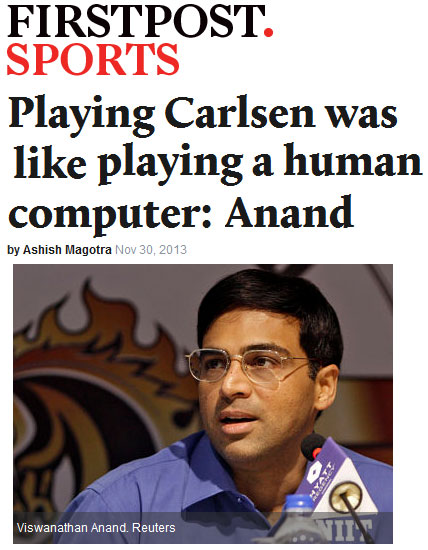

Did it feel like you were playing a computer?

His approach resembles… I hesitate to say… computer. Put him in front of one and he’d lose easily. But he is very confident of his calculating ability – so in that sense… yes, probably like a human computer – if that makes sense.

You have spoken about wanting to play in the Candidates next year. Does this loss change anything? Will your method change? Will you change?

I think the recent trend is away from openings. In a sense, computers have killed the opening phase. There is only so much that you can do. So if anything can be done, it is to rebalance the game. That can only happen by concentrating on the middle and end game. For now though, I have taken a break from chess. Then I got to London for a tournament. Then I take another break – a long break. That’s when I will give it some serious thought – what I want to do and how I want to do it.

Who were Carlsen’s seconds? Who were the men who helped him beat Viswanathan Anand? Who helped him prepare? These are all questions that were asked at various times during the World Chess Championship match. And the Norwegian champs response to most of those questions has been a shake of the head or a simple ‘No.’ This even while Anand came out an revealed K Sasikiran, Sandipan Chanda, Radoslav Wojtaszek and Peter Leko as his seconds before the start of the match.

In an interview with the Hindu after claiming the title, the 22-year-old stuck to his guns and kept a wrap on the identities of his seconds. “It’s mainly my decision. That’s the way I’ve understood it. It’s nice that I am going to play another World championship match (in 2014),” said Carlsen. “It doesn’t mean that I’m not very grateful for their hard work. They have done a wonderful job. I think, it is nice for the future matches not to reveal too much.”

The only name that has come out in the open is GM Jon Ludvig Hammer, who is also from Norway. On Norwegian television — they have talked about what Carlsen looks for in a second: It’s really more on having people around him that puts him in the right mood. Their Elo rating or strengths are of not as much consequence. Hammer has known Carlsen for a while and he was perfect for the job.

Carlsen also took help from computers to help in his preparation. Oslo firm Basefarm used a program that ran a powerful calculator which helped him analyse games. In fact, he had been connected to these powerful servers in India too, and while training in Norway. But there is another human element that is just as important. Seconds can help you prepare for human opponents a lot better than computers. Computers don’t feel the stress of a moment and they can’t pile on any visual pressure on the opponent — which is why Carlsen also depended on two others GMs – Ian Nepomniatchi and Laurent Fressinet.

Sources close to the Anand camp have told Firstpost that they already knew who the seconds were before the start of the match, so there was no mystery there for the Indian GM. Fressinet, 32, is a good friend of Carlsen — which is evident from this Youtube video (a must watch by the way):

He is France number three and he finished second in the European Individual Championship in Plovdiv in 2012. He usually plays for France in team events but gave the European Team Championship a miss this year.

Nepomniachtchi is a 23-year-old Russian chess grandmaster and the 2010 Russian Chess Champion. As of November 2013, he was listed by FIDE as having an Elo rating of 2721. He has worked as a second for Carlsen before (the 2012 London Chess Classic and the Candidates tournament in March) and like Fressinet, he also didn’t play in the European Team Championship this year.

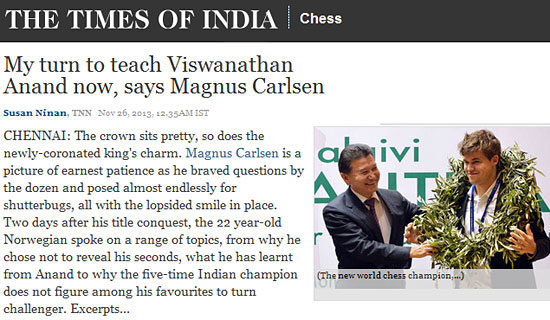

On why Anand does not figure (Carlsen had recently named Aronian and Kramnik) among those he feels could be his next challenger...

Firstly, Vishy will have to figure out if he would want to play in the Candidates tournament. Although he's an all-time great player, his results lately have not been too good and he'll need some time to readjust to be able to come back. It all depends on him now. He needs to figure some things out and if he manages to keep his motivation after this match he will still be a force to reckon with. Right now though I don't think he's the biggest favourite at the Candidates.

On what he's learnt from Anand...

To be honest I've learnt a lot from him in the past, both playing against him and especially while training with him. Just the kind of positions that he understands, the way he would just outplay me like no one else did in several kinds of positions. Also the precision with which he analyses games and positions has been an eye-opener. In this match I showed him in a way that although he's taught me many things in the past, it's probably now my turn to teach him. So, it's safe to say I've surpassed him now.

On whether next year's title match is already on his mind...

Yes, I'm already thinking about it. It is also a reason why I have not spoken much about my current seconds since they could be part of my team then as well. I have the lead in world rankings and the title as well now. I don't think it's my duty to think who will play against me, it should in fact be the other way round. My opponents will have to figure out how to deal with me. I think I will be the man to beat for quite some time now.

On whom he owes his win to...

My family especially my father, team and seconds. They have attended to all my requests, no matter how unreasonable those might have been. My seconds have worked hard and have not slept well so that I would be well prepared. They actually worked harder than I asked them to!

Magnus Carlsen, 23 on Saturday, has achieved the strongest global recognition for any chess player since Garry Kasparov. The Carlsen brand stems from the young Norwegian's newly acquired world title, his all-time No1 ranking and his growing legend of invincibility but also from his non-chess attributes as a cool and hunky sex symbol, a part-time male model and a fertile source of comparisons to Mozart, Justin Bieber or Harry Potter.

For all that, there are still critics who question whether Carlsen is truly in the same bracket as Bobby Fischer and Kasparov, the two established all-time greats. The reservations are based on Vishy Anand's poor form at Chennai, the luck which Carlsen had in the 2012 London candidates and the inflation in the rating system which has developed since the Fischer and Kasparov eras.

Most of all, the unease about Carlsen centres on his playing style, which is very different from the great classical masters of the past. Carlsen certainly knows plenty of hot theory when he needs it, but his preference is to play an objectively level position where his persistent pressure and superior fitness will count, particularly in a long and tiring endgame. In the old days they called it sitzfleisch. Anand's tame approach and his apparent fixation to take on the solid Berlin 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 meant that Carlsen's anti-theory plan was only really tested in game nine, He got away with it then, but Kasparov claimed that Anand had more dangerous ways to press home his fierce attack.

|

|