Winning starts with what you know

The new version 18 offers completely new possibilities for chess training and analysis: playing style analysis, search for strategic themes, access to 6 billion Lichess games, player preparation by matching Lichess games, download Chess.com games with built-in API, built-in cloud engine and much more.

"I was winning."

If there is a more common phrase in chess to express denial, I cannot think of one. Denial? What if it is true? It is all the stronger if indeed it was. Consider this: when you utter that statement, it is to reframe a game that ended in a draw, or a loss. It is to describe the game as winning for you, and the actual result is the lie, the fiction, the universe denying you of what was rightfully yours. In a nutshell, it is to deny the painful reality of the result and replace it with a description that is more comforting.

While this is the most socially accepted denial used, it is also fair to say there are many others. But let's not suggest this is some mental aberration confined to chess. It is human nature, and is seen in sports all over and in life in general.

In this scene from the classic French comic "Asterix at the Olympic Games", the hero loses to the locals and his chief comments "The track was heavy"

Still, imagine the pressure to seek solace in an alternate explanation when you are a world champion faced with a crowd of avid fans.

![]()

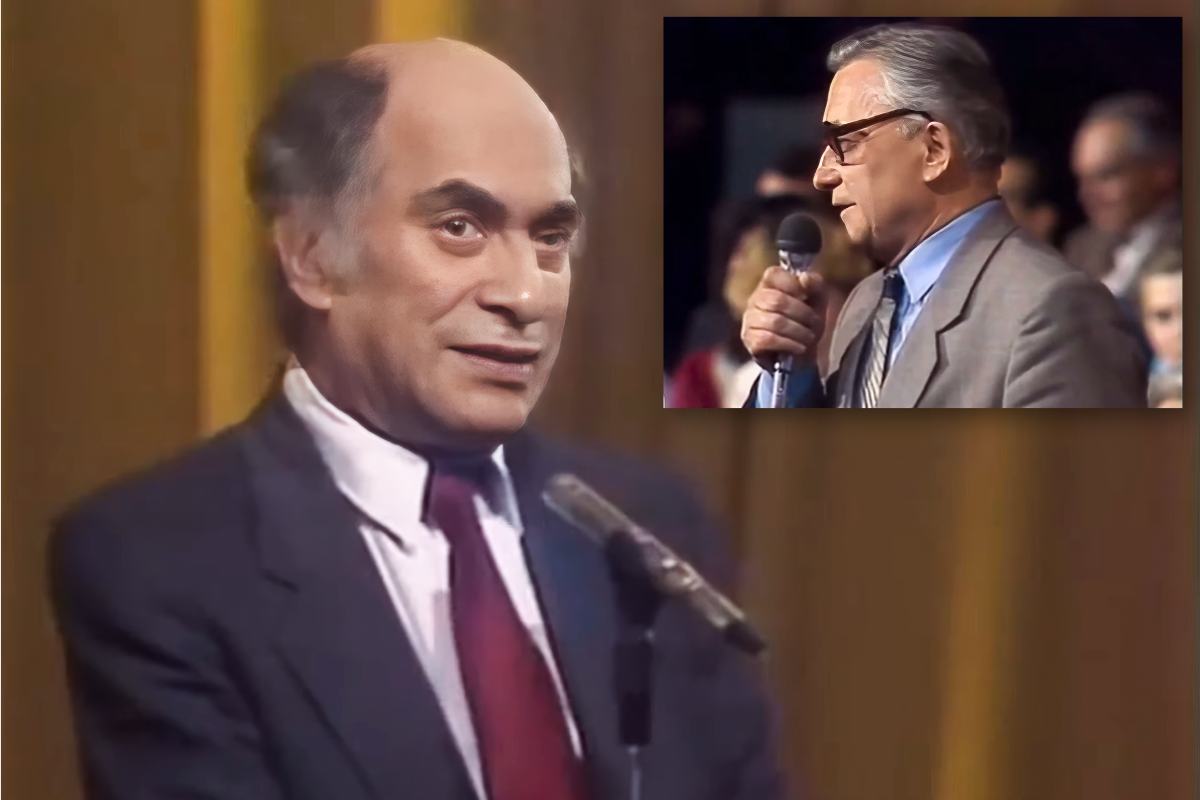

Such was the situation with no less a player than Mikhail Tal. Standing alone on a stage, in front of a packed audience, with television cameras capturing every second, an audience member is given the microphone and asks him point blank:

In 1961, you disappointed us greatly. I’d like to know… well, I think you have cooled down enough since losing that match… How would you evaluate your crushing defeat in the return match [against Botvinnik]?

Imagine the slight knot in his stomach or throat with such a question! It must be pointed out that the Magician from Riga had a fairly easy dodge had he wanted it. It was well-documented that he fell ill during the match with a flu and more importantly, in 2002, Yuri Averbakh revealed that Tal had been having serious health issues, and his doctors in Riga advised him to postpone the match. Botvinnik knew of this too.

![]()

"Explain your crushing defeat!"

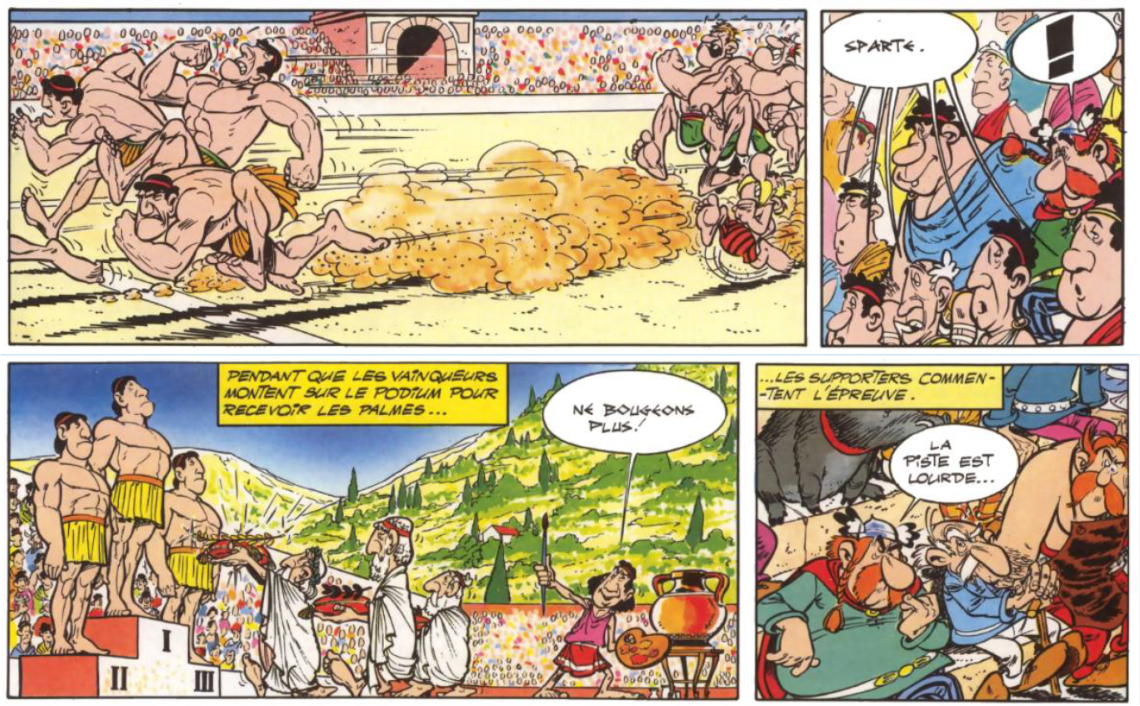

Tal was a keen student of human nature, including his own, and a journalist, and clearly had pondered the question in depth. It must also be pointed out that this is not the 20-something Tal who had just played the match. This is a greyer and far more mature Tal who is being confronted. As such, he replied deadpan:

I have found two reasons – it’s up to you to decide how serious they are. Two very serious reasons that became the… roots of my defeat. The first one: my coach, Honoured Coach of USSR, Alexander Koblenz… he’s not just a chess master, a true expert in chess, psychologist and very good friend… he’s also a singer.

You can imagine the looks of consternation, with a very serious-looking Tal explaining this as if he were finally revealing a long-kept secret!

He studied belle canto in Italy, he’s a lyrical tenor, unlike Smyslov. So, during the first match, before every game we would sit in our room in the Moscow hotel, and he would sing. Neapolitan songs, arias from Italian operas… he sang beautifully. And Botvinnik lived one floor lower. He heard everything. I don’t know why, but during the return match, Botvinnik stayed at his own house, so this psychological trick didn’t work anymore. That’s the first reason.

By now it was clear that Tal's famous imagination was not confined to the chessboard, and even the initial questioner was no doubt wondering whether he was to be the butt of the Latvian's wit as revenge for his confrontational question.

The second reason for my defeat… I had lost three games in a row in the middle of the match, and then finally… No, this happened earlier. I had lost Game 7 and finally found a pencil. A lucky pencil. You can’t even imagine what a lucky pencil means to a chess player. So I managed to win one game in a row after that. I was completely sure that I’d turn the match around very soon. But, sadly, I fell ill after that, caught a flu, and this flu led to disastrous consequences. When I came to play the next game, the pencil had disappeared. Some unknown fan, clearly supporting Mikhail Moiseevich (Botvinnik), took it away, and so I was left completely unprepared for further play.

I almost fell out of my chair laughing at the quip "I managed to win one game in a row after that". The question remains now, is it all just going to be a joke, and will this in effect be his dodge, however witty?

The answer is no. Mikhail Tal is a much bigger man than that, and while he does not hesitate to play with the expectations of human nature and human frailty, even his own, he is able to overcome such things and he continues with breathtaking frankness:

And speaking seriously, you know, all complaints about the unfavorable result of the 1961 match should be addressed to Mikhail Moiseevich Botvinnik (note: he was alive and well at the time of this recording). His preparation was so brilliant. He completely transformed his playing style, and I was absolutely unprepared for that new transformed Botvinnik who opposed me in 1961. Even though he played great in 1960 as well, I lost the 1961 match because Botvinnik played stronger and won.

It must be noted that he is doing more than simply acknowledging Botvinnik outplayed him. He is saying that instead of asking him how he lost to Botvinnik, as if this had been entirely in his control, why not instead ask Botvinnik how he managed to come up with the brilliant preparation that Tal (and his team) never saw coming.

Give credit where credit is due.