Victor Kortchnoi, two-times contender for the world championship, is a piece of living chess history. He is known as one of the greatest fighters in the history of chess. On this DVD he speaks about his life and shows his game.

Korchnoi and Sosonko knew each other well. They are both from Leningrad, Korchnoi was born in 1931, Sosonko in 1943, they first met at a simul. At the beginning of the 1970s Sosonko became Korchnoi's coach but in 1972 Sosonko emigrated from the Soviet Union and when he knew that he wanted to leave the country he stopped the cooperation with Korchnoi to keep his friend from possible political repercussions.

In 1976 Korchnoi also left the Soviet Union — after playing a tournament in Holland he asked for political asylum in Amsterdam. In the following years the two emigrants often met and had close contact but due to Korchnoi's difficult character their relationship was never easy. Sosonko writes:

He didn't accept compromises, and could easily classify yesterday's friends as today's enemies. As a rule, the reason was always the same - at some moment or other, they became in Korchnoi's eyes an obstacle preventing him from gaining the world title. ... It is not that easy to name any of his family, friends or colleagues with whom he never got into an argument. Only grandmasters who worked for him over a very short time avoided this fate. (p. 109-111)

Korchnoi's son Igor said about his father: "If there were various ways to handle a situation, my father always chose the most confrontational approach." (p. 225)

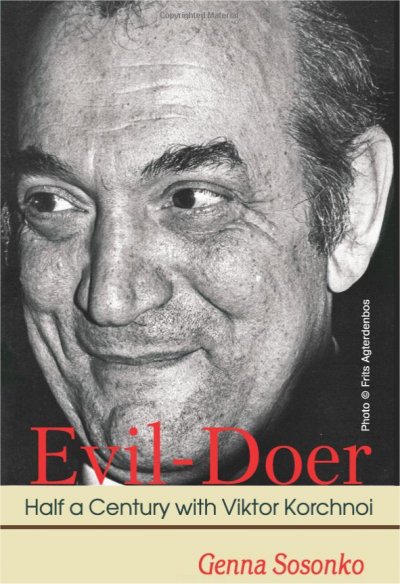

But despite all quarrels and conflicts Sosonko and Korchnoi kept close contact up to Korchnoi's death. In the introduction of Evil-Doer: Half a Century with Viktor Korchnoi (Elk and Ruby 2018) Sosonko writes:

Viktor told me several times: "You are the executor of my will." I'm not sure exactly what meaning he attached to those words, but I consider it my duty to recall everything I know of this remarkable man's life. Especially what only I know. (p. 12)

But Sosonko does not want to write a classical biography as he explains with a reference to Sigmund Freud. In a letter to the German writer Arnold Zweig, a friend of Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis once expressed his reservations about biographies:

Whoever becomes a biographer forces himself to tell lies, conceal facts, commit fraud, embellish the truth and even mask their lack of understanding - it's impossible to achieve the truth in a biography, and even if it were possible, that truth would be useless and you could do nothing with it. (p.12)

Sosonko adds:

I have not attempted to write Korchnoi's biography as such. Rather, this is a collection of memories, or to be more precise still: a collection of explanatory notes and interpretations of incomprehensible or misunderstood events from the complex life of a man whom I knew for nearly half a century...I want to believe that these recollections will not only uncover the motives behind his controversial actions, but will also shed light on his approach to the game, his personality and behavior in everyday life. ...In my reflections on this great player, I wanted to display him, as the English say, warts and all. (p. 12-13)

Though Sosonko does not write a typical biography his memoir still spans the time from Korchnoi's birth to his death.

Korchnoi was born on March 23, 1931 in Leningrad into a Jewish family. Korchnoi's parents separated early, and Korchnoi grew up with his stepmother, the new wife of his father. She helped him to survive the siege of Leningrad in World War II when the German Wehrmacht tried to starve the city. The siege lasted from September 1941 to January 1944 and killed about 1.1 million people — most of them died from hunger.

After the war, Korchnoi discovered chess, in the pioneer palace where Vladimir Zak took him under his wings. Another famous student of Zak is Boris Spassky, with whom Korchnoi had a life-long rivalry. Korchnoi lacked Spassky's talent but he worked like possessed and soon had his first successes. He later says: "I attempted to overcome every obstacle with brute force., I was so sure of myself it was ridiculous." (p. 19)

In 1947 Korchnoi wins the Soviet Junior Championships. Many years later he looked at the games of this Junior tournament and states: "Absolutely no talent! I would never have let that young man into my chess club." (p. 19)

But Korchnoi's hard work, his energy, and his will to win pay off and he gradually becomes one of the best players of the Soviet Union and thus the world. In 1956 he gets the grandmaster title and in 1962 he qualifies for the Candidates Tournament in Curacao. In 1968 he reaches the finals of the Candidates Matches but loses against Spassky. In 1971 Petrosian defeats him in the semifinals of the Candidate Matches, and in 1974 Korchnoi narrowly loses against Anatoly Karpov in the finals of the Candidates Matches.

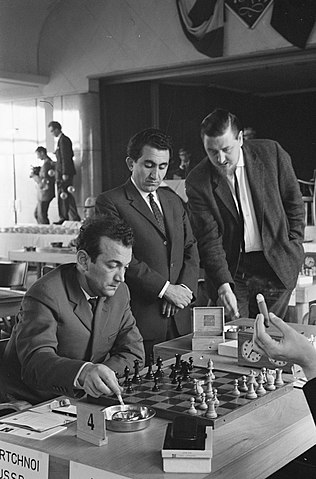

Korchnoi in 1962 at a match between the USSR and The Netherlands. Tigran Petrosian and Jan Hein Donner follow Korchnoi's game. | Photo: Harry Pot / Anefo [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

After the match against Karpov, Korchnoi "gave an interview to Yugoslav newspaper Politika in which he was less than complimentary about the winner and, above all, implied that his defeat was due to pressure from 'higher up'". (p. 63) These statements made the interview political and afterwards, Korchnoi was scathingly attacked by the Soviet chess press in general and by Tigran Petrosian in particular. Korchnoi was afraid of sanctions by the Soviet Chess Federation, and in July 1976 he asked for political asylum in Amsterdam to be able to play chess unhindered.

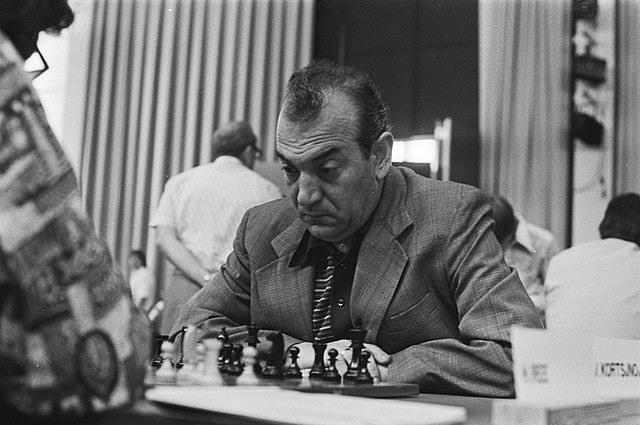

Korchnoi in the first round of the IBM Tournament 1976 | Photo: Rob Bogaerts / Anefo [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Korchnoi's escape to the West is a political humiliation and an insult for Soviet officials and they retaliate with all their power to punish the "Evil-Doer". Korchnoi's name is no longer mentioned in Soviet magazines, Soviet players boycott tournaments in which Korchnoi takes part, and Korchnoi's wife and son whom he left behind in the Soviet Union are put under pressure.

Such conflicts just seem to have motivated Korchnoi even more. He wins the following Candidate Matches and in 1978 he plays in Baguio City, the capital of the Philippines, for the world title against Karpov — at that time Korchnoi is already 47 years old. The match is bitterly contested and both sides fight with a number of dirty tricks but after 32 games Karpov narrowly wins 6 : 5 (draws did not count) and defends his title.

Only one week after the match Korchnoi plays first board for Switzerland at the Chess Olympiad 1978 in Buenos Aires. He scores 9.0/11 and wins gold for the best result on board one.

In 1981, Korchnoi again plays a World Championship match against Karpov but this time loses 7 : 11 without much chances. Korchnoi's dream to become World Champion seems to have come to an end — however, he still is one of the world's best players.

Korchnoi before the start of the first game of the match against Karpov in Merano | Photo: Isabel Hund (Isabel Hund) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

How I became World Champion Vol.1 1973-1985

Garry Kasparov's rise to the top was meteoric and at his very first attempt he managed to become World Champion, the youngest of all time. In over six hours of video, he gives a first hand account of crucial events from recent chess history, you can improve your chess understanding and enjoy explanations and comments from a unique and outstanding personality on and off the chess board.

In 1983 he is supposed to play against the young Garry Kasparov in the semifinals of the Candidate Matches but the match between Kasparov and Korchnoi at first does not come about because FIDE and the Soviet Chess Federation cannot agree on a venue for the match. As a result, FIDE declares Korchnoi to be winner by default. But three months later the match still takes place. FIDE and the Soviet Chess Federation found an agreement and Korchnoi also agreed to play against Kasparov — in turn, the Soviet boycott against him was lifted. But Korchnoi could not cope with the powerful play of the up-and-coming Kasparov and lost the match 4 : 7. Two years later Kasparov was World Champion, the youngest in the history of chess.

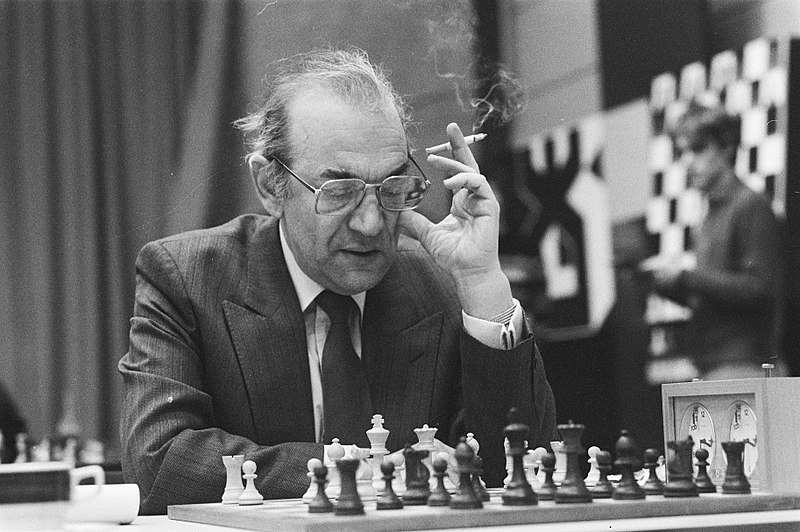

Korchnoi at the Hoogovens tournament 1985 | Photo: Rob Croes / Anefo

Korchnoi played his last Candidates Match when he was 60 years old, in 1991, in the quarterfinals of the Candidates Matches. Korchnoi lost 2½ : 4½ against Jan Timman.

Age took its toll on Korchnoi even though his passion for chess was boundless. Sosonko writes: "He played it with passion, in a frenzy, and chess for him was more important than for anybody else whom I encountered in the game. And I encountered a lot of people." (p. 252)

The older he got the weaker his chess became, and his passion turned into an obsession. Korchnoi once liked to ski enthusiastically, could dance throughout the night, liked to play cards, and was interested in history, politics, and literature but when he got older he only focused on chess.

He still achieved remarkable successes — e.g. he became World Senior Champion in 2009 and at the Gibraltar Open 2011 he defeated Fabiano Caruana in a remarkable game with Black — but he was simply not as good as he used to be, though hardly any player in the history of chess has been as strong in old age as Korchnoi.

Korchnoi at the Chess Olympiad 2008 in Dresden | Photo: Frank Hoppe, (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons

His playing strength dwindled but he still understood the game better than most and this often provoked him to lecture younger players — even if they had just won against them. Korchnoi even attacked the very best:

The first DVD with videos from Anand's chess career reflects the very beginning of that career and goes as far as 1999. It starts with his memories of how he first learned chess and shows his first great games (including those from the 1984 WCh for juniors). The high point of his early developmental phase was the winning of the 1987 WCh for juniors. After that, things continue in quick succession: the first victories over Kasparov, WCh candidate in both the FIDE and PCA cycles and the high point of the WCh match against Kasparov in 1995.

Running time: 3:48 hours

During Anand's ascent to the top in the 1990s, Korchnoi was quite disparaging about the young Indian's play. Anand actually complained that, even though he had won about a dozen games against Korchnoi with no losses, Korchnoi would tell him each time that he didn't have a clue how to play chess. Nevertheless, the Indian's actual performances in the 2000s forced Korchnoi to eventually become one of Vishy's biggest fans. (p. 270)

Korchnoi was also dismissive of Carlsen. After Carlsen had shared first prize at the tournament in Wijk aan Zee 2008 — at the age of 17 — Korchnoi said: "I don't have a great opinion of Carlsen. He's an unusually weak player, just lucky, he doesn't understand much about strategy." (p. 264)

But Korchnoi was full of contradictions — which showed when he later revealed the real reason for his grudge against Carlsen: "I am jealous of Carlsen! He knocks them all out with one punch, it really is incredible. To reach that level, I had to put in many years of hard work, yet it's easy for him." (p. 268)

Such stories and anecdotes bring the many facets of Korchnoi's character to life — and Sosonko's book is full of such stories. Sosonko's reflections, comments, background information, and his benevolent view of the strenghts and weaknesses of Korchnoi connect and unite these stories and turn Evil-Doer into a very readable and entertaining book.

Sosonko and Korchnoi in Zurich 2015 | Photo: Evgeny Surov

At the end of the book Sosonko quotes Boris Spassky who once talked with the Canadian Grandmaster Kevin Spraggett about his old rival:

[Spassky] began to list Korchnoi’s many qualities:

- Killer Instinct (nobody can even compare with Victor’s ‘gift’)

- Phenomenal capacity to work (both on the board and off the board)

- Iron nerves (even with seconds left on the clock)

- Ability to Calculate (maybe only Fischer was better in this department)

- Tenacity and perseverance in Defense (unmatched by anyone)

- The ability to counterattack (unrivaled in chess history)

- Impeccable Technique (Flawless, even better than Capa’s)

- Capacity to concentrate (unreal)

- Impervious to distractions during the game

- Brilliant understanding of strategy

- Superb tactian (only a few in history an compare with Victor)

- Possessing the most profound opening preparation of any GM of his generation

- Subtle Psychologist

- Super-human will to win (matched only by Fischer)

- Deep knowledge of all of his adversaries

- Enormous energy and self-disciplineThen Boris stopped, and just looked at me, begging for me to ask the question that needed to be asked….I asked: ‘But, Boris, what does Victor lack to become world champion?‘ Boris’ answer floored me: "He has no chess talent!"

Korchnoi died June, 6th 2016, in Wohlen, Switzerland, where he lived. Maybe he indeed did not have as much chess talent as Spassky. But due his enormous will to win, his boundless love for chess, and his controversial character Korchnoi is one of the most interesting and influential players in the history of chess. With Evil-Doer Sosonko gave this colourful and ambivalent personality a fine memoir.